Events

Partner event | Multilevel constitutionalism beyond the state

You are cordially invited to join a guest session on 16 October 2024, 12.45 CEST/16.15 IST, Jindal Global Law School (JGLS), online via MS Teams (in English).

Joining link [click here]. Session poster [link here].

Synopsis: One of the fundamental challenges of European constitutionalist discourse concerns the relationship between the law of the European Union (EU), the law of the European Convention on Human Rights and constitutional law of the EU member states. Here, member state constitutional courts have begun to set limits to European (Union) integration, triggering a discussion on the interpretation and legitimacy of such a practice. Is this development sustainable or does it threaten to undermine the functioning of European (Union) integration? How can experiences and insights from constitutionalist discourse beyond Europe help understand (or critique) these developments?

Speakers:

- Professor (Dr.) Markus Böckenförde (Central European University)

- Sarthak Gupta (Supreme Court of India, in personal capacity)

Bios:

- Markus Böckenförde is Associate Professor and Chair of the Comparative Constitutional Law Program at CEU’s Department of Legal Studies. Before joining CEU, he was the Founding Executive Director of the Centre for Global Cooperation Research at the University Duisburg-Essen (2012-2018). As head of the advisory team to the Policy Planning Staff at the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (Bonn-Berlin) he gained some first-hand practical experience in political decision making processes (2011-2012). From 2009-2011, he was Program Officer and temporarily Acting Program Manager for the Constitution Building Project at International IDEA, Stockholm, Sweden. Between 2001-2008 Markus Böckenförde was the Head of Africa Projects and a Senior Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (MPIL) in Heidelberg. In 2006-2007, he was seconded by the German Foreign Office to the Assessment and Evaluation Commission (AEC) in Sudan as its legal expert. The AEC has been mandated to support and supervise the implementation of the Sudanese Comprehensive Peace Agreement. From 1995-1997 he was research assistant to Justice Professor Steinberger, the German delegate to the Venice Commission. Markus Böckenförde holds a law degree and a PhD (summa cum laude, awarded with the Otto Hahn medal of the Max Planck Society) from the University of Heidelberg and a Master of Laws degree (distinction, valedictorian) from the University of Minnesota as well as the equivalent of a Bachelor degree in political science (University of Freiburg). During the Constitution Building processes of Sudan, Somalia, Tunisia, and Libya, he has worked together with the pertinent constitutional assemblies and has been otherwise involved in the processes in Afghanistan, Nepal,Yemen, and Myanmar. He is the co-author of International IDEA’s Practical Guide to Constitution Building (also translated into Arabic, Myanmarin, and Vietnamese) and several Max Planck Manuals on Constitution Building. He has worked as a consultant on constitutional issues for the UN, UNDP, GTZ, DAAD, International IDEA, the German Foreign Office, the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, and the Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

- Sarthak Gupta serves as a Judicial Law Clerk-cum-Research Associate at the Supreme Court of India and is currently working with Justice Sandeep Mehta, Judge, Supreme Court of India. He holds a B.A.L.L.B. (Hons.) degree from the Institute of Law, Nirma University, India. He is also a Helton Fellow at the American Society of International Law. His academic blog posts appeared on IACL-AIDC blog, Verfassungsblog, EJIL Talk! and elsewhere.

The guest session is sponsored by the JGLS and co-organized with Aman Gupta, LL.M. (Lecturer, JGLS) and Varishtha Singh (student, JGLS).

Partner event | The policy-making of a quasi-constitutional court: The European Court of Justice

You are cordially invited to join a guest talk followed by a discussion on 25 September 2024, 12.45 CEST/16.15 IST, Jindal Global Law School (room T1-G03) and online via MS Teams (in English).

Joining link [click here]. Poster [link].

Synopsis: The European Court of Justice, like most courts, renders decisions on the basis of the cases and questions that are brought before it. However, that is not the only role it has been ascribed, for it is also a quasi-constitutional tribunal, a federal arbiter, and an important policy maker. This talk will elaborate on the important policy choices the court has made in the process of constitutionialising the EU legal order. We will have a comparative look at the Court’s powers and discuss its role in shaping EU social policy.

Speaker bio: Franziska Pupeter is an SJD candidate and researcher at the Central European University. Her fields of expertise include comparative constitutional law, EU constitutionalism and EU social policy and she also works on a research project on the labour rights of platform workers. She earned her law degree from the University of Vienna and an LLM in comparative constitutional law from the Central European University. In her EU law-focused research, she endeavours to bridge and combine doctrinal legal research with interdisciplinary approaches.

Suggested background reading: Barnard, Catherine, 'EU ‘Social’ Policy From Employment Law to Labour Market Reform', in Paul Craig, and Gráinne de Búrca (eds), The Evolution of EU Law (Oxford, 2021), 678-708.

The guest talk is co-organized with Aman Gupta, LL.M. (Lecturer, Jindal Global Law School) and Varishtha Singh (student, Jindal Global Law School).

Partner event | EU Constitutionalism and the Role of Courts: A View from the Periphery

You are cordially invited to join a guest talk followed by a discussion on 2 September 2024, 10.35 CEST/14.05 IST, Jindal Global Law School (room T3-G43) and online via MS Teams (in English).

Synopsis: To fully understand the role of courts within the European constitutional landscape, we must examine not only their constitutional function, but also how they are influenced by broader Europeanization processes. This talk will explore the interplay between national and supranational courts through several case studies, with a special focus on Central and Eastern European countries.

Speaker bio: Arnisa Tepelija is an SJD candidate in Comparative Constitutional Law at Central European University in Vienna. Her work is focused on judicial independence in South Eastern European countries and processes of Europeanization thereof. She holds a Master of Science Degree in Law from the University of Tirana, and an MA degree summa cum laude in Advanced European and International Studies from Centre International de Formation Européenne (CIFE) in Nice, Berlin and Rome. She is an expert, researcher and author of many papers related to the rule of law, anti-corruption and EU Integration, and has been engaged as consultant and advisor to international organizations and governments on these matters.

Suggested background reading: Sadurski, Wojciech (2012). Constitutionalism and the Enlargement of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, xvii–xxviii.

The guest talk is co-organized with Aman Gupta, LL.M. (Lecturer, Jindal Global Law School) and Varishtha Singh (student, Jindal Global Law School).

Expert witnessing in the social sciences in the 21st century: Experiences, challenges and perspectives

Date and time: 11 June 2024, 9.30-11.30am CEST in hybrid format (in-person component at the Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Arts, Dean's Hall--room no. G140)

Language: Slovak (Czech), without translation

The aim of the event is to discuss and share the knowledge about the current state of expertise in the social sciences in Slovakia, including historical and comparative contexts. The event connects decision makers from the judicial and executive power and the legal profession with experts as well as academia, in order to deepen mutual understanding of diverse perspectives and the state of knowledge both in science and in legal and decision-making practice. The event also introduces, for the first time in the Slovak environment, the theory of "cultural expertise", which has been on the rise in the international literature since 2015 and is currently the subject of a project aimed at creating a global network of actors interested and engaged in the field of expertise in the social sciences (K-Peritia COST Action, Cultural Expertise Junior Network, working group members for Slovakia: Dr. Matej Medvecký, Dr. Max Steuer).

The event takes place as part of the "Talking Courts" project hosted by the Department of Political Science of Comenius University. Registration possible until June 9 (for in-person participation) or June 10 (for online participation) at https://forms.office.com/e/rxWf7CgAEy. In case of any questions, please write to max.steueruniba.sk.

Opening

- Mgr. Matej Medvecký, PhD. | Institute for Military History in Bratislava

- Max Steuer, M.A., LL.M., PhD. | Comenius University in Bratislava, Department of Political Science

Introductory remarks

- JUDr. Petra Príbelská, PhD. | Judge and Senate Chairperson, Supreme Administrative Court of the Slovak Republic

- Mgr. Sylvia Hvizdošová | Director of the Department for Expert Witnesses, Translators and Interpreters, Ministry of Justice of the Slovak Republic

Introducing the conceptual framework of “cultural expertise” for thinking about expert witnessing in the social sciences in the 21st century

- Max Steuer, M.A., LL.M., PhD. | Comenius University in Bratislava, Department of Political Science

- Mgr. Matej Medvecký, PhD. | Institute for Military History in Bratislava

Experience of registered expert witnesses in the social sciences in Slovakia and Czechia – discussion

- PhDr. Mgr. Petr Jurek, Ph.D. | Head of the Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of West Bohemia in Pilsen

- Mgr. Pavol Kosnáč, MSt., PhD. | Director of the DEKK Institute and researcher, Institute of Ethnology and Social Anthropology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava

- Mgr. Matej Medvecký, PhD. | Institute for Military History in Bratislava

- doc. JUDr. PhDr. Ivo Svoboda, Ph.D., LL.M., DBA. | Criminology Department of the Academy of the Police Force in Bratislava

Broader perspectives and comments, general discussion

- MUDr. Norbert Moravanský, PhD. | Comenius University in Bratislava, Institute of Forensic Medicine – lead consultant of the “Institute for Forensic Medicine Expertise”

- doc. Mgr. Helena Tužinská, PhD. | Comenius University in Bratislava, Department of Archaeology and Cultural Anthropology

- doc. PhDr. Zdeněk Vojtíšek, Ph.D. | Head of the Department of Religious Studies, Charles University, Prague

Concluding remarks

- Mgr. Matej Medvecký, PhD. | Institute for Military History in Bratislava

- Max Steuer, M.A., LL.M., PhD. | Comenius University in Bratislava, Department of Political Science

Event report

On June 11, 2024 (Tuesday), an event aimed at exchanging experiences and perspectives related to the topic of expert witnessing in the 21st century took place on the premises of the Comenius University, Department of Political Science (Faculty of Arts). The event was organized thanks to the support of the project “Talking Courts” (grant of the U.S. Embassy in Slovakia) and in thematic synergy with the COST Action “K-Peritia - Cultural Expertise Junior Network” coordinated by the Royal Anthropological Institute in London (principal investigator: prof. Livia Holden), in which Slovak Republic also has its representation through Dr. Matej Medvecký (Institute of Military History) and Dr. Max Steuer (Department of Political Science, Comenius University).

Upon the initial greeting of the organizers, Dr Medvecký and Dr Steuer, speeches by JUDr. Petra Príbelská, PhD., a judge and the senate chairperson at the Supreme Administrative Court of the Slovak Republic, and Mgr. Silvia Hvizdošová, Director of the Department of Expert Witnesses, Interpretership and Translation at the Ministry of Justice of the Slovak Republic followed. These speeches consequently framed the event’s course, elucidating on the Ministry’s perspective on the questions of expert witness activity and the process of their cooperation with courts.

Judge Príbelská began her speech by citing the founder of the law and literature movement (James Boyd White) in the context of emphasizing the tension between practice and theory, between the law and the facts as the central characteristic of legal life. Afterwards, she shared her experience (as a member of a five-person senate) with the refferal made by the attorney general of the Slovak Republic in the matter of the dissolution of the political party Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia, stressing that the Supreme Court of the Slovak Republic has no competence to initiate its own evidence collection process, which include expert witness instruction. Since the involvement of expert witnesses was not suggested by the parties, and the petitioner (the attorney general) provided minimal evidence with an insufficiently complex analysis, the court could not execute such procedures (in contrast to, for instance, administrative punishment).

Director Hvizdošová highlighted the need to increase the number of expert witnesses in social sciences and improve their compensation, the low rates of which are mainly a consequence of a lack of finances for the coverage of the activity of expert witnesses in certain departments of the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice. New challenges brought about by an evolution of social realities in the 21st century will likely only increase the value of expert witnessing, making debates on methodological approaches, the question of objectivity, and technological advances increasingly more complex. Director Hvizdošová pointed out that the Ministry is interested in supporting (various) projects and initiatives.

The introductory speeches were followed by a presentation of the basic premises and goals of the COST Action "K-Peritia," which connects the theory of "cultural expertise" with the aims of gathering and digitally making accessible empirical data on expert activities in the social sciences and humanities across various countries and branches of law, as well as the creation of an international certification system for assessing the qualifications of expert witnesses that could subsequently be recognized by national authorities.

A discussion of expert witnesses registered in Slovakia and/or the Czech Republic followed. It was initiated by PhDr. Petr Jurek, Ph.D. (Head of the Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of West Bohemia in Pilsen), who is also presiding over one of the few expert witness institutes in the Czech Republic focused on social sciences. The institute, since its founding, has worked on completing several dozen expert evaluations. Dr. Jurek spoke on the crucial contributions of the legal reform in 2019 in the professionalization of the activity of expert witnesses. However, the said changes did not necessarily transfer to better compensation, especially after taking into account the costs of regular expert witness activity, thus emphasizing that the individuals involved are not motivated primarily by money. Many other discussed challenges also parallel the situation in Slovakia. Furthermore, it happens that extremists are changing their rhetoric and said acts are more difficult to evaluate, especially with cases of more sophisticated “hate crimes” and “hate speech”. At the same time, Dr. Jurek advocated for the model of expert witness institutes as being better prepared for reducing the number of objections received and for effective reactions to them, as opposed to a model of individual experts working on cases.

The sole expert witness in the area of religious extremism in Slovakia, Mgr. Pavol Kosnáč, MSc., Ph.D. (Director of the DEKK Institute and member of the Institute of Ethnology and Social Anthropology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences) outlined several problems with which expert witnesses in the country are currently confronted. Among the most prominent problems are the difficulty of the entrance exam (especially its reliance on specific, often memorisation-heavy knowledge) and the bureaucracy surrounding the experts' activities (keeping an expert witness logbook), aside from the lack of proper financial compensation. Dr. Kosnáč also spoke of the unique problems that arise from his activities as a beginner expert witness in a recently established field. Such a situation is problematic in how it puts an inadequate amount of pressure on Dr Kosnáč as a professional because, due to being the sole expert in the subfield, it is clear who would be approached on matters of religious extremism in Slovakia.

An expert witness in social sciences has to be prepared for objections that do not necessarily attack the academic validity of their findings, but rather objections raised by one of the parties in the proceedings to question the findings or to open complicated moral dilemmas. Such issues limit the motivation of beginners in the field, who could otherwise view the opportunity as a chance for professional development and a way to exercise social responsibility. Dr. Kosnáč additionally spoke of how transdisciplinary cooperation is utilized, especially in cases where various disciplines would tend to favour different conclusions (for instance, political science, in his view, is more concerned with questions of security, while religious studies tend to be more sensitive to cultural contexts).

Mgr. Matej Medvecký, PhD. (Institute of Military History) emphasized that in the vast majority of cases he works on, the Police Force of the Slovak Republic instructs the expert witnesses, which transfers into how complications linked to work with private contractors looking for a specific outcome are usually kept at a minimum. The approach of public institutions tends to be constructive, even though occasionally, they pose legal questions that cannot be answered by the expert witness, and the timeframe in which the expert witness should complete their work is often unrealistic, resulting in delays. Dr. Medvecký perceives the infrastructure and support mechanisms put in place to support expert witnesses in Slovakia to be insufficient, as the examples available to follow were essentially limited to the Czech Republic, and he also spoke of the absence of training given to expert witnesses for conducting hearings. Expert witnesses in the social sciences are often mistakenly viewed as jacks of all trades, being faced with questions that go beyond the scope of the expert witness statement. The speaker also highlighted the trend of penetration of militant phenomena via social networks especially during the last two years.

In the discussion that followed, doc. JUDr. PhDr. Ivo Svoboda, PhD., LL.M. (Police Force Academy in Bratislava), the first expert witness in the field of political extremism in Slovakia (since 2017) along with Dr. Medvecký) and the Czech Republic (since 2009) pointed out problems relating to the inability of the contractors to formulate their questions for the expert witness clearly enough, and to the pressures the expert witnesses are faced with. He outlined his experiences with a case from the Czech Republic when a political party was being dissolved and the involvement of expert witnesses was notable. Additionally, Dr. Svoboda confirmed a recent rise in trends that complicate the process of creating expert witness assessments, also including cases pertaining to incitement to armed attacks.

The focus of further discussions were the positives and negatives that arise from the establishment and operation of expert witness institutes. A cross-disciplinary approach and the doing away with a model where a single expert is connected to a specific case (a sort of “depersonalization”) can indeed be beneficial for the quality and effectiveness of the process of assessment, while they do not lead to the loss of personal input from specific individuals. Doc. PhDr. Zdeněk Vojtíšek, Ph.D. (head of the Department of Religious Studies, Charles University) shared the experiences of experts in religious studies with the media, where he sees a tendency to view such expertise as a kind of “sectarian defence”, instead of the media making a deliberate effort to get acquainted with the case itself and the expert witness involvement in it. Such accusations are much harder to face for an individual expert witness, especially with the absence of a larger expert community that could provide an additional opinion on the matter. Occasionally, they also transfer into objections relating to partiality that, as Director Hvizdošová had emphasized from the perspective of the Ministry as the expert witness supervisory authority, are statistically mostly raised by natural and legal persons. The said risk, however, does not mean that expert witnesses cannot publish and be involved in other forms of academic public communication related to their field of expertise.

The concluding segment of the discussion included a broader engagement with the topic, also involving MUDr. Norbert Moravanský, PhD., a forensic doctor (CU Institute of Forensic Medicine, chief consultant in the expert witness body “Institute of Forensic Medical Expertise”) and doc. Mgr. Helena Tužinská, PhD. (CU Department of Archeology and Cultural Anthropology).

Dr Moravanský, as an expert witness with extensive experience (more than 5000 assessments completed via the expert witness institute since 2006) emphasized the difficulty of assessing cases in social sciences and noted the importance of cooperation among the expert witness community in general, while also evaluating the positives and negatives of creating expert witness institutes. While such institutes can protect against undesirable pressure from parties with vested interests or contractors, and they have the invaluable benefit of an internal mechanism of second opinions and the ability to provide training for young expert witnesses, their activities do not negatively affect the significance of quality of the work of their experts. Logically, interpretative expert assessments in social sciences will predominantly be questioned in the contemporary post-factual age, and the professionality of this line of work needs to be ready for such questioning to arise, while being prepared to react to it. This applies in cases of ad hoc expert activity as well, where the questioning discussed is even more commonplace. Dr. Moravanský argued for mock trials and hearings of expert witnesses as a way to better the practical skills of these professionals, and advocated for the use of past faulty or problematic assessments, case studies and practice questions as study materials for experts across various fields.

Associate Professor Tužinská opened the topic of the long-term rise of the level of tension in society, also manifested in how the expert witness profession and academia operate under the pressure of vested interest of outside parties. She emphasized the importance of using plain language alongside specialized terminology by expert witnesses, as the addressees of cultural expertise (especially in cases where translations are needed as well) are usually not acquainted with the given terminology. The activity of translators and interpreters also has great influence in cases of “intercultural translation”, which transcends the frame of purely technical communication. She used the example of terminological framing of the term “social group”. A judge escaping persecution in their home country “lost their judicial identity in translation” when involved in a case at the Regional Court in Bratislava. In clarifying terms to the interpreter, the judge ruled out professional identification as a possible criterion for belonging to a social group.

Judge Príbelská reacted by pointing out that, paradoxically enough, some of the most difficult cases are being addressed by beginner judges in first-instance courts, who perhaps do not have enough experience, which also underscores the importance of professional training for the judicial profession.

At the conclusion of the event, the organizers invited the attendees to participate in the activities of the aforementioned COST Action, as well as to carry on with this form of dialogue, not least in relation to current challenges that demand and will demand, in the upcoming years, the involvement of expert witnesses.

The report was compiled by Max Steuer, assistance provided by Lukáš Schvantner (intern at Talking Courts, student at the Department of Political Science, Comenius University), translated to English by Samuel Michlík.

Discussion on Slovak constitutionalism, public policy and protection of democracy in Bratislava

On Tuesday, 7 May 2024, the Department of Political Science of the Comenius University hosted a discussion with a multidisciplinary study group of scholarship holders from the Hans-Böckler Foundation, including two scholarship holders from the University of Göttingen. The panel moderated by Campbell MacGillivray, M.A. (PhD candidate, University of Göttingen), included Professor Emília Sičáková-Beblavá (Institute of Public Policy, Comenius University) and Dr. Max Steuer (Department of Political Science, Comenius University and 'Talking Courts' project coordinator). The discussion covered a wide range of issues, including modern history of Slovakia and its legacies of non-democratic practices, the founding of the Slovak Republic in 1993 after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, the consequences of the dissolution of Czechoslovakia on the text and practices of the Slovak Constitution as well as public policy-making. The panelists and participants engaged with, among others, the role of scrutinizing and improving specific public policy areas as well as the utilization of both grand and local narratives of constitutionalism and democracy, the positioning of Slovakia in the Visegrád region, Central Europe including Germany and the European Union more broadly, or the avenues to protect democracy in Slovakia by institutions (including the Slovak Constitutional Court, media, think tanks and NGOs) and the public at large in light of contemporary developments. The discussion emphasized the democratic foundations of Slovakia and its achievements in the last 30 years, but also enduring unaddressed public policy issues that combine with contemporary illiberal narratives and represent a risk for its democratic future.

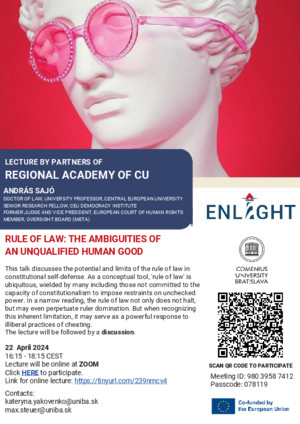

Rule of Law: The ambiguities of an unqualified human good

Event implemented as part of the Regional Academy of the university alliance ENLIGHT on 22 April 2024, 16.15-18.15 CEST, in English without translation.

Speaker: András Sajó

- Doctor of Law (Hungarian Academy of Sciences)

- University Professor, Central European University

- Senior Research Fellow, CEU Democracy Institute

- Former Judge and Vice President, European Court of Human Rights

- Member, Oversight Board (Meta)

Report: On 22 April 2024, Professor (Dr.) András Sajó, University Professor of Central European University, former Vice President of the European Court of Human Rights and member of the Oversight Board (Meta) delivered an ENLIGHT Regional Academy talk at the Department of Political Science of the Comenius University to an audience comprising a mixture of students of political science, philosophy, law and other disciplines, and academics from Slovakia and abroad. The ENLIGHT talk unfolded in partnership with the ‘Talking Courts’ project run at the Department of Political Science of the Comenius University, and was held also as a guest session in an undergraduate political science course devoted to understanding and critically discussing foundational political concepts, including the rule of law.

The lecture masterfully combined an introductory overview of the concept of the rule of law with reference to Western legal traditions, and critical reflections on how the rule of law is used and referred to in contemporary societal discourses. The rule of law is a fashionable term denoting, at its core, the restriction of arbitrariness of governments’ powers, hence contributing to overall legal and political decency. However, beyond this general meaning, disagreements persist over what the rule of law requires and what it can help achieve.

Disagreements in political discourse have more sophisticated mirrors in legal philosophy. In his talk, Professor Sajó built on Harvard-based philosopher Lon Fuller’s criteria of the ‘internal morality of law’, emphasizing particularly that of congruence between officials’ (political leaders’, state administrators’) conduct and the requirements of the law. The rule of law, so understood, has liberating effect on citizens, as it enables individual conduct within the boundaries set by the rules.

Professor Sajó then discussed how judicial independence, while not requiring one specific model of organization of justice, is required by the separation of powers as a key principle to constrain the arbitrariness of governments’ powers. The diverse modes of organization of the justice system permitted by judicial independence, however, have been abused by cheaters—political leaders with vested interests to enhance (their) arbitrary power.

To address this weakness of the formal conception of rule of law without having to undertake the difficult, perhaps impossible task to achieve consensus over the substantive content of the rule of law, Professor Sajó, in line with his recent writings, proposes for the rule of law to “go militant”. The key stakeholders in this transformation are judges who, while often reluctant to engage in what they see are political struggles, and are not typically trained to perform well in them, also typically have the tools at their disposal within the (positive) law. Following the jurisprudential analogy made by Joseph Raz, for Professor Sajó, the rule of law is akin to a knife—it may be useful for cutting bread and distributing it around the table, but may also be abused to kill an innocent person.

The ensuing Q&A session generated several student questions on the operation of illiberal as opposed to authoritarian regimes, the distinction between militant rule of law and the established concept of ‘militant democracy’, the similarities between the contemporary attitudes to the rule of law in Hungary and in Slovakia after the 2023 general elections there, or the degree to which some, particularly libertarianist, interpretations of individualism might themselves fuel tendencies of regime change that undermine the rule of law. The discussion also featured remarks by the course conveners from the Department of Political Science, Professor (Dr.) Darina Malová and Dr. Max Steuer. Professor Malová discussed the institutionalist versus more agency-centred perspectives on analysing social life, and the differences that these yield for understanding the conduct of decision-makers (including judges) in individual cases. Dr. Steuer highlighted the linkages between judicial conduct and the (particularly) legal academia, and the extent to which the viability of the militant rule of law might be affected by the structure of legal education and attitudes of academic elites.

The organizers express sincere thanks to Professor Sajó as well as to the ENLIGHT Regional Academy for supporting the event.

________________

Synopsis: This talk discusses the potential and limits of the rule of law in constitutional self-defense. As a conceptual tool, 'rule of law' is ubiquitous, wielded by many including those not committed to the capacity of constitutionalism to impose restraints on unchecked power. In a narrow reading, the rule of law not only does not halt, but may even perpetuate ruler domination. But when recognizing this inherent limitation, it may serve as a powerful response to illiberal practices of cheating.

The hybrid event was available online via the Zoom platform (link). The poster is available via this page (link). The in-person component took place in room N416 on Múzejná 2, 810 00 Bratislava.

Cooperation on the workshop "European Union and the rule of law"

The national round of the Slovak Human Rights Olympics engaged with the role of judiciaries in democratic societies in 2024 as well, including through a specialized workshop for the participants on the topic of the European Union and the rule of law on April 17, 2024. The guest of honour of this workshop from among active judges was Dr. Barbara Pořízková, Vice-President and Judge of the Supreme Administrative Court of the Czech Republic, who is also a member of the panel provided for by Article 255 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("255 Comité").

The discussion during the workshop was joined by Mr. Radim Dvořák, Deputy Head of the European Commission's Representation in Slovakia and Head of the Political Team, while the moderator was Associate Professor Erik Láštic, Head of the Department of Political Science, Comenius University in Bratislava, and member of the "Talking Courts" project team.

We are delighted that the organizing committee of the Human Rights Olympics devoted dedicated space to this key topic also in 2024.

Photos © Human Rights Olympics.

Demystifying the Court of Justice of the European Union: An Introduction

The purpose of this talk is to engage with a, for a broader audience, often mysterious and underestimated institution of the EU: the Court of Justice (CJEU). Despite being not only one of the core EU institutions as per the Lisbon Treaty and, according to several observers, the ultimate constitutional interpreter in the EU, it generally receives scant attention beyond specialized legal circles. Nevertheless, its rulings impact not only EU legislation, but also the daily lives of EU citizens and residents, at times becoming a source of inspiration outside the EU context as well. By introducing the core functions, principles and controversies associated with the CJEU's influential role within the EU institutional system, the talk contributes to demystifying the Court beyond niche communities of lawyers, and thereby also to raising critical questions on its current functioning and challenges.

Presenter: Aman Mehta, LL.M. candidate, Central European University (Vienna), Advocate, Supreme Court of India

Moderator: Dr. Max Steuer, Comenius University, Department of Political Science

Schedule and format: April 8, 2024, 12.35-14.45, in person at the Comenius University, Faculty of Arts (classroom N217). The event is held in English.

Seminar on the Supreme Court of India and the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka

Guest Session in hybrid format on ‘Social Change, Constitutional Adjudication and the Constitutional Core' organized at the O.P. Jindal Global University, Jindal Global Law School. Date and time: 27 October 2023, 12.45-14.30 CEST / 16.15-18.00 IST.

Speakers:

Dayaar Singla

Dayaar Singla is an Advocate practising primarily at Delhi. He has served as a Judicial Law Clerk to the CJI Dr. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud and started his career at Trilegal. He is as a Senior Editor for India’s oldest public law blog, Law and Other Things. Dayaar graduated from NALSAR University of Law with three gold medals.

Ayesha Wijayalath

Ms. Ayesha Wijayalath is a final year Scientia Ph.D. student in the Faculty of Law and Justice at the University of New South Wales, Australia, focusing on sovereignty in Sri Lanka and the Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendment doctrine. Prior to her Ph.D., she worked as a Research Associate at the Centre for Asian Legal Studies, National University of Singapore (NUS). Ayesha graduated from NUS with an LLM specializing in International and Comparative Law. She is also an Attorney-at-Law in Sri Lanka.

Guest session on the Ukrainian Constitutional Court

Guest session in hybrid format on: ‘Constitutional Court and Constitutional Adjudication in Ukraine', organized at the O.P. Jindal Global University, Jindal Global Law School.

During this session, the status, main functions, principles of the activities, tasks of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, its composition and place in the system of state bodies of Ukraine will be presented. It is planned to analyze the main subjects of constitutional appeal and complaint, as well as the procedure for consideration and decision-making, key methods of interpretation and constitutional adjudication in Ukraine. During the session, participants will have a unique opportunity to ask their questions and discuss the most important topics regarding the peculiarities of the functioning of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, during martial law in particular.

Dr Kristina Trykhlib is an Associate Professor at the Department of Theory of Law at the Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University in Kharkiv (Ukraine). She has been teaching courses in State and Law Theory, Legal Deontology, Comparative Law, Human Rights, European Convention on Human Rights, and Legal Writing. Her research interests lie at the European integration, harmonization of legislation, rule of law, legal interpretation and reasoning, human rights standards. She is an author of one monograph and more than 50 scientific and methodological publications in the field of law in Ukrainian, Russian, English and Polish languages, as well as one of the authors of the Ukrainian Encyclopedia of Legal Terms, published in 2016. She is also a Member of Non-Governmental Organization NAMU – National Association of Mediators of Ukraine. Kristina Trykhlib has taken part in the implementation of international scientific projects and was a Visiting Researcher at Warsaw University, Jagiellonian University in Poland, Innsbruck University (in Austria), and the Polish Academy of Sciences. She was awarded the Diploma of the Winner of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Prize for the Most Talented Young Scientists in the Field of Basic and Applied Research, Scientific and Technological Development in 2018 for her scientific work "Harmonization of Ukrainian Legislation and the EU Law: Approximation of General Legal Terminology".

Recommended readings:

- Kristina Trykhlib, ‘Law-Making Activity in the Case Law of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine’, International and Comparative Law Review 19, no. 2 (2019): 27–75, https://doi.org/10.2478/iclr-2019-0014.

- Ÿ Yu. Yakymenko, ed., Ukraine: 30 Years on the European Path (Kyiv: «Zapovit» Publishing House, 2021), particularly 183-196, 253-260.

Guest session on the Indonesian Constitutional Court

Guest session in hybrid format on: ‘Constitutional Courts and the Protection of Human Rights: A Comparative Perspective’, organized at the O.P. Jindal Global University, Jindal Global Law School.

M. Lutfi Chakim is a constitutional researcher at the Constitutional Court of Indonesia. He holds an LLB degree from UMM in Indonesia and an LLM degree from the Seoul National University, South Korea. During his study period in Seoul, he conducted research at the Association of Asian Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Institutions (AACC), Secretariat for Research and Development, managed by the Constitutional Court of Korea (2018-2020). His research interests lie in comparative constitutional law and international human rights. He has published in a range of peer-reviewed journals, books, and magazines. His most recent publication is ‘The margin of appreciation and freedom of religion: assessing standards of the European Court of Human Rights’, The International Journal of Human Rights (Volume 24, 2020).

Speaker’s publications relevant for the session:

- M. Lutfi Chakim, ‘Organizational Improvement of the Indonesian Constitutional Court: Reflections on Appointment, Supervision, and Dismissal of Justices’, International Journal for Court Administration 12, no. 1 (2021): 1–10, https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.308.

- M. Lutfi Chakim, ‘Freedom of Speech and the Role of Constitutional Courts: The Cases of Indonesia and South Korea’, Indonesia Law Review 10, no. 2 (2020): 191–205, https://doi.org/10.15742/ilrev.v10n2.605.

Courts, Democracy, Human Rights, and US Foreign Policy: Talking Courts at the 25th National Round of the Slovak Human Rights Olympics

The final round of the 25th anniversary of the Human Rights Olympics in Slovakia, a national-wide competition for high-school students that contributes significantly to education for human rights, democracy and the European Union in Slovakia has offered an extraordinary opportunity to discuss with some of the most motivated and committed high school students in the country as well as several recognized experts, including judges and NGO representatives, in human rights protection in Slovakia. The final round took place in person after several years of hybrid formats due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequently the Russian invasion of Ukraine. One of the four traditional workshops offered to the participants on the second day of the competition (19 April 2023, Omšenie, Slovakia) was dedicated to the Talking Courts project. An overview of the workshop’s agenda (in English and in Slovak) can be found at the Human Rights Olympics website (link).

The format of the workshop presented a unique conversation between a US federal court judge, a foreign policy practitioner and an academic. Representative of the US Embassy in Bratislava, Political and Economic Officer Mr Shiv Srikhant delivered the introductory remarks on the role and significance of human rights in US Foreign Policy, highlighting some of the challenges that diplomatic specialists face particularly in case a particular US leadership is not supportive of advancing human rights protection.

The focus on public policy was followed by the intervention of Professor Cornell W. Clayton, DPhil. (Oxon), C.O. Johnson Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service, Washington State University, who was also Fulbright Specialist at the Comenius University in Bratislava, Department of Political Science, in April 2023. Professor Clayton highlighted the dominant paradigm in US law and courts scholarship which captured significant portion of the debate on the role of courts in the protection of human rights and democracy, known as the countermajoritarian difficulty (A. Bickel). As he pointed out, however, this idea of courts opposing the democratic majority needs to be nuanced, as it is questioned both by empirical evidence and the theory of democracy. Professor Clayton emphasized that judges’ self-acknowledgement of the role of their experiences and philosophies in judicial decision making, while trying consciously to minimize this influence as a form of self-restraint, is central for advancing their role and public presentation as protectors of human rights.

Yet, Professor Clayton also warned against presenting all kinds of societal controversies as human rights disputes (referring to the works of M. A. Glendon). Such ‘overkill’ of the human rights language may serve to hide the genuinely political choices that need to be made in a democracy through civil dialogue and persuasion in search of a consensus, and be ultimately counterproductive in advancing progressive human rights agendas.

The ’external’ point of view by Professor Clayton was followed by the ‘internal’ point of view by Judge David G. Campbell, Senior United States District Judge for the District of Arizona and Chair, U.S. Courts’ Committee on International Judicial Relations. Judge Campbell acknowledged the dilemmas that judges sometimes face when their reading of the law in place does not allow them to render a judgment that they themselves would deem to be fair. Nevertheless, Judge Campbell, who, in his stellar career, also clerked at the US Supreme Court, highlighted that, in a state under the rule of law, it is essential for judges to adhere to the law.

While Judge Campbell argued for maintaining a shaper distinction between law and politics, he raised powerful examples where he himself, or other judges in the US, succeeded to protect human rights against the violations of the limitations of public powers by state organs. The student participants were particularly inspired by these cases, and connected them to several contemporary public policy controversies in the US, including gun ownership and associated instances of gun violence, the death penalty as well as judicial independence.

The ensuing discussion has generated questions directed to Professor Clayton and Mr Srikhant as well, in which the participants explored connections between the human rights rhetoric and practices of political leaders and the role of courts in shaping those and preventing the spread of unjustified rights restrictions and neglect towards vulnerable members of our societies.

The Talking Courts project team wishes to express thanks to the distinguished speakers, Mrs Stacey Campbell, all participants for their active engagement, and the U.S. Embassy in Slovakia, represented at the event by Mr Shiv Srikhant and Political Specialist Ms Gabriela Šaturová, as well as the J. William Fulbright Commission for Educational Exchange in the Slovak Republic which supported the stay of Professor Clayton. Particular appreciation is due to the organizers of the Human Rights Olympics, the National Commission of the Olympics led by its Chairwoman, Dr Dagmar Horná, supported by eight regional coordinators (one high school teacher per each of the Slovak regions) and several other experts, as well as the support team of the Olympics including Mr Patrik Nalešnik and Mr Lukáš Gejdoš, for their trust and support of the strong presence of the Talking Courts initiative from the Olympics. We would also like to acknowledge the presence of several distinguished guests, including the Chairperson of the Slovak Supreme Court Dr Ján Šikuta and human rights attorney Dr Michal Davala, recently endorsed by the Judicial Council as a nominee to the newly established Administrative Court in Bratislava.

Discussions of Judge Campbell with high school students

During his short visit in Slovakia Judge David G. Campbell, senior United States District Judge for the District of Arizona and Chair, U.S. Courts’ Committee on International Judicial Relations visited three secondary schools in Bratislava and engaged in lively discussions with their students (around 80 students in total). The discussions took place at the following secondary schools:

- Secondary grammar school, Grösslingová 18 (GAMČA), Bratislava

- Secondary grammar school of Jur Hronec, Bratislava

- Secondary grammar school, Ladislava Sáru street, Bratislava

The Talking Courts project team gratefully acknowledges the collaboration with the leadership of these schools as well as with the contact persons among the teachers, in particular Mgr. Michal Bohuš, Mgr. Jana Gabrišová and Mgr. Martin Vanca.

Report from the discussion with Judge Campbell at the "Gamča" (Secondary grammar school Grösslingová 18), 18 April 2023, author: Adam Melicher (student)

I recently had the esteemed privilege of being invited to attend an event where Federal Judge David G. Campbell, who currently serves as a United States District Judge for the District of Arizona, delivered a talk. The speech was predominantly centered upon explaining the fundamental role and importance of law in preserving peace and social stability. Through the examination of three exemplary cases, Judge Campbell highlighted the critical role of maintaining law and order in a functioning judicial system and emphasized the importance of upholding legal principles to ensure justice for all.

The first case involved an inmate who filed a federal lawsuit against a group of prison guards, alleging that they brutally beat him without any real reason. The incident was reportedly captured on video camera. However, when the inmate’s attorneys requested a copy of the video as evidence, they were informed that there was no such video. A significant piece of evidence in the court case was a memorandum written by one of the prison guard supervisors, which suggested disciplinary action against the guards and cited the video footage of the incident as the reason for the punishment. This confirmed the existence of the video, allowing it to be used as evidence in court. The jury eventually awarded the prisoner a sum of several thousand dollars in compensatory damages, as well as punitive damages. Despite the fact that the inmate was serving time for crimes he previosly committed, this just goes to show that everyone is equal before the law and that the law protects everyone.

In the second mentioned case the Arizona's Governor Jan Brewer prohibited DREAMers (undocumented youth) from obtaining driver's licenses in 2012 due to a federal ban on offering them benefits. However, in 2014, the judge ruled that the ban violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution and allowed DREAMers to get licenses. Despite Arizona’s appeal, the ban remained lifted, emphasizing that no one is above the law.

The third and last case was “New York Times Co. v. United States (1971)” in relation to the exposure of classified information pertaining to the extent of military operations in Vietnam. The highest US judicial authority, the Supreme Court, resolved this issue by determining that this injunction against publication was a violation of the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. This landmark case underscores the vital significance of the separation of powers among the Judicial, Executive, and Legislative branches of government, emphasizing the need for both interdependence and checks and balances among these entities.

Towards the end of the event Judge Campbell dedicated time to address questions concerning the discussed cases, as well as other topics related to the judicial system. The questions in the lively discussion included (but were not limited to):

- the main difference between the judicial system of the United States and Slovakia;

- Judge Campbell’s path towards his appointment as a federal judge;

- the main difference between the trial process in the United States and in Slovakia;

- several issues connected with gun use and gun ownership both here in Slovakia but mainly in the United States;

- the competent decision-making authorities entitled to ban guns in the United States;

- the mechanisms and reasons behind constitutional change in the US concerning abortion;

- the current legal status at the federal and state level in the US concerning abortion;

- the difference between assault and battery.

In conclusion, the discussion with Judge Campbell was an insightful and informative experience. It emphasized the importance of law and the judicial system in maintaining peace and social stability. Through the examination of three exemplary cases, Judge Campbell highlighted the fundamental role that the law plays in protecting individuals and ensuring justice for all. I greatly enjoyed this speech, and I would recommend everyone to attend such opportunities when presented. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Judge Campbell for sharing his knowledge and experience with us.

Towards democratic judiciaries

REPORT

On April 17, 2023, the two-panel plenary event of the ‘Talking Courts’ initiative was hosted by the Department of Political Science of the Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Arts, in collaboration with several Talking Court project partners including the J. William Fulbright Commission for Educational Exchange in the Slovak Republic and O.P. Jindal Global University, Jindal Global Law School. The event brought together a distinguished group of speakers and participants around the table, from academia, state institutions (notably apex courts and public institutions dedicated to fundamental rights protection and monitoring), and domestic and international non-governmental organizations.

The event was the highlight of the initiative aimed at transcending the traditional silos, whereby exchanges about courts are relegated to law faculties and communities of lawyers instead of more interdisciplinary audiences, or at best, if presented from a Political Science perspective, engaged with through narrow angles of behavioral approaches which conceive of judges as partisans akin to political actors in the executive or the legislature.

The engagement with a richer account was supported through the dialogical elements between the US and the Central European (particularly Slovak, but also Czech, Hungarian, Croatian and Romanian) perspectives. While, undoubtedly, significant differences persist in the design of the federal US judiciary and justice system and the Central European jurisdictions hailing predominantly from a civil law tradition, this distance at one level translated into openness to mutual learning and appreciation of those fundamental principles that apply for judicial decision making regardless of institutional developments.

The event consisted of two sessions, one investigating the role(s) of judges in democracies more broadly, while the other zooming in on the roles of judges as educators and the educated, against the backdrop of education about judiciaries in the society at large.

The sessions adopted the model of main speakers opening the debate but accompanied by a series of short interventions, with the aim to highlight what diverse participants consider to be the key issues associated with the discussion themes and how these themes resonate with the jurisdictions they are most familiar with.

Politics, Trust and the Language of Democracy

The event was opened by the Vice Dean for International Relations of the Comenius University, Faculty of Arts, Dr. Aneta Világi, who emphasized the relevance of the topic for Slovakia in 2023, due to the low trust in the judiciary and the rule of law. In his opening remarks, Talking Courts project coordinator Dr. Max Steuer underscored the concept behind the event as embracing a richer meaning of politics than only partisanship and bias, following the philosophy of Hannah Arendt. Courts, in this reading, are impartial, but political institutions committed to the safeguarding of freedom for individuals and communities who interact with the public sphere.

The opening remarks were followed by the speech of the President of the Supreme Court of Slovakia, Dr. Ján Šikuta, who referred to the Israeli Supreme Court President Aharon Barak. Barak, in his book The Judge and Democracy, identified two key roles for a democratic judge: bridging the gap between law and society, and protecting the constitution and democracy. For President Šikuta, who was also judge at the European Court of Human Rights, democracy is not merely formal, residing in the sovereignty of the legislature and free and fair elections, but it is also ‘real’, i.e. ‘expressed in the notion of separation of powers, rule of law and its fundamental principles of the independence of the judiciary and human rights.’ Such reading of democracy requires the judges to continuously educate themselves, and, when engaging in interpretation, to consider ‘not only the wording of the law, but also its meaning and purpose’ in the social context. The Supreme Court in Slovakia also plays a role in unification of the law and publication of authoritative opinions, which is even more important due to the diversity on the bench, a key value for quality judiciary.

The first session chaired by Dr. Kirsten Roberts Lyer (Associate Professor, Central European University, Department of Public Policy) generated a debate between experiences from the US, Slovakia and international courts. Judge David G. Campbell, Senior United States District Judge for the District of Arizona and Chair, U.S. Courts’ Committee on International Judicial Relations, following up on President Šikuta’s remark on legal interpretation, presented four key considerations for a judge in a democracy:

1. to ‘faithfully interpret and apply the law enacted by the representative branches of the government’, meaning, ‘as [the law] was intended’ by the representatives, and ‘not [to] rewrite the law’;

2. ‘when necessary in a democracy […], to apply the rule of law to check the other branches of the government when they violate laws or when they step beyond their proper boundaries’;

3. ‘to apply the rule of law to protect individual rights and to protect individual freedom, even when that may require a judge to rule against a government or to rule against public opinion’, because ‘individual liberty lies in the heart of democracy’;

4. to ‘take the second and third steps […] even when it is contrary to public opinion and even when it is vigorously opposed by the government that the judge is ruling against’.

However, according to Judge Campbell, for the judges to be able to perform their role in the above manner, their societal context must support judicial independence from the other branches of government, judicial integrity as ‘honesty, fairness and transparency on the part of the judge’, judicial restraint (‘modesty where [judges] need to stay within their proper role’ and readiness to ‘check themselves’ as well) and public acceptance of the courts’ roles.

Professor Cornell W. Clayton (C.O. Johnson Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute, Washington State University; Fulbright Specialist, Comenius University in Bratislava, Department of Political Science) underscored his designation as a political scientist and as such as thinking about the judiciary as ‘intricately connected to a broader political system, and less autonomous from that political system’. He presented the view that the role of the judge is shaped by the type of court they are appointed to: apex courts raise very different questions about the role of judges and democracy than the lower courts’ judges. Where for the former, the concern is much more about the fundamental principles of constitutional governance and democracy, i.e., democratic principles and principles of justice, whereas the lower courts are more concerned about the fair application of law and legal documents in the case present before them. Confining his remarks to apex courts, Professor Clayton pointed to ‘a gap between the internal perspective of how judges operate on these courts and the external perspective of what the public and other political leaders think these judges are doing in court.’ While judges typically claim to be ‘neutral umpires of politics’ and ‘not engaged in politics’ (referring to the statement of US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts during his confirmation hearings in 2005), the public perceives them as making political choices. More than 80 years of (predominantly US-centered) social research points to the alignment between apex court decisions and the political ideology of their judges (notably stemming from the work of US academics Segal and Spaeth). The reasons for this gap have to do with the dependence of law, at some level, upon underlying political values, which give purpose to the practice of law, but are also behind an inherent degree of indeterminacy in law.

Criticizing those who believe in a ‘neutral formula’ (following Herbert Wechsler), Professor Clayton urged, especially in common law systems, to advance ‘a different language’ to talk about what these courts do, one that is not so relying upon legal, formless ideas of legalism, and one that is much more tied to democracy and doing justice. This shift, both when judges talk about themselves and when others talk about judges, matters because, for judges to have authority, it does not suffice that they persuade political leaders and the public opinion about the correctness of their decisions in terms of law. Rather, they need to show that these are correct also in terms of justice and democracy, which ‘legal formalism’ is unlikely to be able to achieve. Moreover, ‘legalistic terminology’ obscures that courts are making decisions about what is the ‘meaning and practice of democracy’ in their respective societies, and if they retreat into the language of legalism, they are not educating the public about why we should protect these values, why some values are in a democracy are more important than others, and how courts and judges think.

The two US speakers’ perspectives were followed by the Judge and Section President of the Supreme Administrative Court in Slovakia (a court operational since 2021), Mgr. Michal Novotný, and prominent Slovak rule of law activist and attorney, Mgr. Eva Kováčechová, both underscoring some of the systemic issues from the perspective of experiences with the Slovak judiciary. Judge Novotný began by raising a concern with the appointment model of Slovak judges, where judges themselves play a prominent role. This risks the ‘judicial branch replicating itself’, of the current judges in the system, instead of allowing for new ideas and approaches.

Despite this concern, Judge Novotný sees the benefit of Slovak judges protecting democracy which, echoing President Šikuta, he does not see merely as the role of the majority, but also ‘the rule of law, which is essentially what a judge can count on in a democracy where he/she is not democratically elected’. This is ultimately necessary for the judge to fulfill the dictum of adjudicating according to the law. Raising the example of the acquittal of the suspected murderer of the journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, the speaker noted that due process needs to be adhered to and quick judgments of the public must not be followed by courts without proper evidence and despite the risk that the public might see the court as ‘hindrance’ to justice due to the latter’s insistence on procedural standards.

Yet, the intertwining of the rule of law and democracy does not mean that judges do not need public trust. This is low in Slovakia also due to ‘huge gaps and huge walls between the judiciary on the one hand, and the civil society on the other’. Overcoming them requires judges to publicly admit that they are ‘neither gods, nor have superpowers’, and are prone to errors as any other human being. Yet, judges committed to their role are, same as in any other profession, ‘trying their best’ and are ‘open to the public checking this performance’. Judge Novotný voiced the concern of this call to openness being misunderstood and feared from by some judges as a road towards undermining the authority of the judiciary but, in fact, it is the only avenue to maintaining and buttressing that very authority.

Attorney Kováčechová devoted her remarks to outlining three concrete ways to improve the Slovak judiciary. In her view, the judicial selection procedures need to emphasize integrity more than only formal knowledge, as otherwise ‘there are people who are judges who should never become judges’. Secondly, more attention is needed to calibrating disciplinary proceedings, such that they are not used as a weapon against judges who do not share the same positions as some of their senior colleagues, and yet also scrutinize breaches of ethical conduct. This may lead to complicated rules from the perspective of the public, but they are nevertheless important for advancing ethical conduct in the Slovak judiciary and judicial integrity. Thirdly, Slovak judges should work on their communication skills with the public to build mutual trust, especially in cases of high public interest, and indeed be open to public scrutiny. The decision alone is not enough to be published; judges need to be able to explain, when delivering a judgment, why they decided the way they did. For example, in a recent Slovak case of a reckless drunken driver who killed five students, the first-instance judge did not order a custody sentence during the criminal trial because he did not see the legal grounds for it to be fulfilled. The ‘public hate against this judge’ was widespread, he even received death threats. This, according to Kováčechová, was triggered partly by the judge publicly explaining the decision only after some time, and not immediately in the moment when it was announced.

Dr. Antal Berkes, public international lawyer and Lecturer at the University of Liverpool, opted to focus on the jurisprudence of regional human rights courts in the context of electoral systems and judicial independence as two key features of democracy that these adjudicative bodies engage with. Regional courts are ‘aware of the national systems’, but also of the ‘global context’. The very establishment of regional human rights courts was to respond to antidemocratic developments, such as civil wars or totalitarian governance. Courts analyze both global and national context, and their starting point to think about democracy is often a procedural one, focusing on the right to fair trial, or based on the right to vote in particular.

Referring to cases of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which in his view try to ‘educate about democracy’ through these cases; for example, the latter court, in an advisory opinion, has underscored the significance of gradual development towards democracy, that may be undermined without sufficient safeguards even under the conditions of free and fair elections. In Berkes’ view, the increased number of significant cases pertaining to right to fair trial in Hungary and Poland indicates how regional human rights courts aim to contribute to slowing down autocratization in these countries particularly through references to fair trial and judicial independence. This is also a way to recognize the long-term effects of transformations on the judiciary, which may persist even long after elections and potential power transitions in the executive and the legislature. Ultimately, for Berkes, democratic judiciaries are also about dialogue, with courts engaging with the case law of each other, citing each other’s cases, even beyond particular jurisdictions (such as interaction between the regional human rights courts). Yet, they know strategically that they are not ‘fourth instances of national courts’ and cannot go too far in infringing sovereignty which could prompt backlash and non-compliance.

Dr. Mátyás Bencze, Professor or Law and Senior Research Fellow from Hungary, in his short intervention underscored that the phenomenon of judges following public opinion or priorities of particular political leaders that was warned against by several previous speakers could be called ‘judicial populism’. He considered judicial populism to be on the rise due to the increased public pressures on the judges and the latter’s need for public legitimacy. But it is the wrong answer to the dilemma of the judge, because it is often not, in fact, democratic, emerging from the public at large, but pressed by particular media and political elites who claim to speak on behalf of the public. Furthermore, it may easily backfire, with the judges being seen as increasingly biased and untrustworthy.

Within the short time left in the session, participants raised questions particularly on judicial reform that would help reduce the distance between judges and the public, without compromising judicial independence. Dr. Berkes pointed to the importance of links between regional human rights courts and civil society, which may bypass member state governments and unfold transnationally. National judges’ participation in cases handled by regional human rights courts may help the latter’s authority, and President Šikuta highlighted several mechanisms which are already in place in Europe in this context. Judge Campbell emphasized that restoring trust when it is missing in any relationship takes time and effort, the starting point is ’turning down the temperature’ in the political dialogue, avoid talking too quickly too negatively about the courts particularly by the political elites. This avoidance of inherent skepticism about the judiciary’s performance as it is often being depicted was identified as crucial by Judge Novotný as well. ‘Norms of stability and civil discourse’, in the words of Professor Clayton, are needed, regardless of whether in a civil or a common law system.

Courts and Education: Don’t Teach (Only) the Law, Teach Democracy, Teach Justice

The second session chaired by Associate Professor Erik Láštic (Head of the Department of Political Science, Comenius University in Bratislava) encompassed three interconnected dimensions on the relationship between judiciaries and education: education of judges, judges as educators and education of the broader public about judiciaries.

On education of judges, Judge Campbell noted that there are relatively rigorous education programs and quality publications for US federal judges with an important role played by the Federal Judicial Center. Moreover, even ‘baby judges’—recently appointed US federal judges—are seasoned lawyers frequently taking the bench after decades of experience in the legal profession. While these training programs are not mandatory, many judges make use of them. Even at the level of many US states there are impressive educational programs (for example, run by the Judicial College of Arizona for state judges in Arizona).

Professor Clayton agreed that judges can be of great value for education of the younger generation, and that this practice is not uncommon in the US. When it comes to legal education, however, despite the longer democratic trajectory in the US as compared to Slovakia, systemic problems arise here as well. Law students are not sufficiently trained to ‘read more broadly outside (of law), to read about history, to read about democratic theory, to read about how democracies and principles of democracy and justice are essentially politically contested idea and to deal with how we contest those ideas.’ In his view, a narrow conception of legal ethics dominates in the law schools, where the focus is on lawyer-client relationship but not on the broader responsibility of lawyers towards the political and constitutional system as a whole; they are not taught that they have obligations that are just as important as representing their clients, obligations to protect the fundamental principles of a democratic, constitutional government. This has, as its consequence, the existence of many legal professionals who do not feel commitment to contribute to the broader civic space. The education about the US Constitution as purely a legal document, rather than a political document, contributes to this malaise, as well as the limited diversity of former professional careers and experiences of US judges, particularly at the apex courts.

Dr. Zuzana Vikarská, Assistant Professor at the Masaryk University in Brno, pointed to the peculiarity of the post-communist context, where many older judges have not had subjects in school that even remotely enabled them to think about broader societal issues. While there are avenues how they can ‘catch up’, these are rarely mandatory, and hence not all judges undertake them. Younger judges, in turn, sometimes struggle due to the all-encompassing nature of legal education, which offers limited options to specialize from early on for those who have an ambition to become judges (as opposed to occupying another profession) already during their legal studies.

A critical voice towards the current state of university education was also articulated in the discussion with the audience. Dr. Helena Tužinská (Associate Professor at the Department of Ethnology of the Comenius University) argued that university education sometimes appears as training in incomprehensible language that creates a form of communication accessible only to other legal professionals, who consequently lose the skill to be able to explain matters to the public. This was underscored by Dr. Viliam Figusch, former head of the Council of Europe office in Slovakia, with an anecdote that, in a well-written decision, 90 per cent should be understood by everyone and only 10 per cent should require higher competence to engage with.

Dr. Peter Čuroš (Assistant Professor, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland) shared a perspective on the Slovak context of judicial education. Here, a key role is played by the Judicial Academy of the Slovak Republic, which regularly invites Slovak and international experts as well as other judges to foster Slovak judges’ qualifications. At the moment, there is little scrutiny of the work of the Judicial Academy and its contribution to judicial education. For future judges, however, the university is a key setting, and ‘if we want to have the judges towards democracy, we have to train the students to be democratic judges’. Building on the tradition of critical legal scholarship, for Čuroš, university education entails ideological choices (in the sense of signifiers), including on whether and how to teach about democracy. This is often missing at Slovak universities, even at the level of critiquing judicial decisions rather than taking them as ‘given’, as canons, which need to only be built on. University education should also foster respect, in a sense that judges show appreciation towards the parties instead of treating them as their subordinates, and avoid discriminatory remarks in the courtroom and their decisions. Judges do not need to write a doctoral dissertation on all issues they decide, but they should be versed in writing decisions such that not only experts can read them.

With respect to judges as educators, several speakers pointed out that education is often one of the few or even the only exception which legal regulation allows judges to engage in simultaneously to their profession. Yet, besides questions whether they may do so commercially, there is lack of systematic support or rewards for judges engaging in educational activities, which means that only some do, on a voluntary basis and on the top of their official responsibilities. Referring to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s emphasis on listening and learning from others, Judge Flack-Makitan highlighted why not only high court judges, but all judges ought to engage in educational initiatives. Professor Marieta Safta (Professor of Constitutional Law, Titu Maiorescu University Bucharest, Faculty of Law, Romania, and former assistant magistrate and chief of the assistant magistrates at the Romanian Constitutional Court) praised internship programs sometimes offered by courts which allow students directly to interact with judges, as well as legal education at schools based on direct interactions of pupils with members of the legal professions. Furthermore, she intervened on the significance of cooperation between constitutional judges and academia. Though not a panacea, collaborative fora that encompass both sitting judges without an academic appointment and academics without a position directly at the court are helpful for mutual support and even improvement of legal interpretation. Here, judges are both educators and the educated at the same time.

Judge Campbell noted the scaling back of civics education in US schools, because of which many students complete their basic education without having an opportunity to understand how the government works. For courts, it is difficult to make themselves widely known to the younger generation without broader support from the educational system. Judges can engage in this agenda after their retirement, as was the case of US Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, or in addition to their core commitments—for example, the Federal District Court of Arizona has a committee of judges ‘the sole purpose of which is to try increase public education by sponsoring programs for high school students coming to courts, or judges and lawyers going to schools.’ The National Constitution Center in Philadelphia also coordinates with judges and lawyers for them to appear by video in classrooms around the country and elucidate court operations. But a few one-hour classes, however important, cannot replace systematic education.

The broader lack of understanding of judicial roles contributes to misperceptions about the judiciary when it is ‘judged by everyone’, or unrealistic expectations from it that no party would ever be disappointed by a fair judicial decision. According to Judge Ksenija Flack-Makitan from the Commercial Court in Varaždin, Croatia, this is tied to the broader lack of civic education; ‘most citizens of the EU think that democracy just means going to a place to cast votes periodically […] if the citizens don’t understand the basics of democracy, they won’t understand what rule of law means, and with that attitude, we cannot change the perception of judges’ work’.

The public obtains insights into judiciaries channeled through regular and increasingly also through social media, but judges and court staff are rarely trained to effectively master these tools, and, especially in smaller countries such as Slovakia, there is insufficient infrastructure and interest to support specialized journalism and reporting about courts’ work. Journalists are, consequently, a key constituency for trainings about the roles of courts and their day-to-day operation.

As Judge Campbell pointed out, a few high-profile cases decided by the apex courts often disproportionately shape the public images of judiciaries: ‘if our citizens could see the work that is done in the vast majority of cases where judges are really trying to get it right and where, in most cases, they go get it right and it is deliberative and it is thoughtful, and it is clear they (the citizens) would have a far different view of the justice system than the one they get by hearing about a few sensational cases that get into the media or the big political issues’.